Greetings to all on Juneteenth—which we celebrate tomorrow.

Juneteenth is short for “June Nineteenth.” It marks the day when federal troops arrived in Galveston, Texas on June 19, 1865 to take control of the state and ensure that all enslaved people be freed. Note that this was a full two and a half years after the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation on Jan. 1, 1863.

A year ago, on June 17, 2021, Juneteenth officially became a federal holiday. Nationwide, it now commemorates the end to slavery in the United States.

You might be asking yourself what place North Yarmouth has in the commemoration of Juneteenth. Doesn’t seem that we have had a very diverse population in years past, or today, even.

However. As Jazmin Kreimer wrote in Saturday’s Press Herald, “If July 4 celebrates our independence as a nation, and Juneteenth commemorates the emancipation of enslaved Americans, these two holidays can represent a twin celebration of freedom that embodies the value that Americans hold highest: freedom for all.

So, yes—North Yarmouth should and does celebrate Juneteenth. And let’s remember that our town did not escape the legacy of enslavement.

Slavery and the North Yarmouth Economy

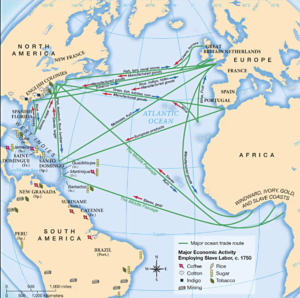

Remember that early North Yarmouth was part of Massachusetts until 1821, and present-day Yarmouth was part of North Yarmouth until 1849. And early North Yarmouth participated in and profited from the Triangular Trade—of which slavery was a part.

Remember that early North Yarmouth was part of Massachusetts until 1821, and present-day Yarmouth was part of North Yarmouth until 1849. And early North Yarmouth participated in and profited from the Triangular Trade—of which slavery was a part.

On the first leg of their three- part journey, European ships brought manufactured goods, weapons, and liquor to Africa in exchange for slaves; on the second, they transported African men, women, and children to the Americas to serve as slaves; and on the third leg, they exported to Europe the sugar, rum, cotton, and tobacco produced by the enslaved labor force. Yarmouth ships were participants in this trade. In fact, many in present-day Yarmouth, with its coastal population, were not in favor of abolishing slavery, mainly because some were a part of the Triangular Trade and the abolishment of slavery would hurt their businesses. There are even newspapers from the South sent to Yarmouth sea captains that have survived through the years.

Slave Owners

North Yarmouth families also owned slaves. From 1736-1763, Rev. Nicholas Loring served The Church Under the Ledge, formerly located on Route 88 in present-day Yarmouth. Loring owned two slaves—a father and daughter, Cuff and Billinder.

Several years later Rev. Tristram Gilman became the pastor of The Church Under the Ledge. He and his wife Elizabeth owned a slave, Phillis, who was given to Elizabeth by her father in 1771, probably as a wedding gift.

Tristram and Elizabeth came from wealthy aristocratic families in which slave-owning was common, but despite Loring’s slave ownership, enslavement was uncommon in North Yarmouth—only three other townspeople were known to have owned slaves. This may have been because most residents could not afford slaves, rather than because they were ideologically opposed to slavery.

Some church members were not happy with the Gilman family’s enslavement of Phillis—especially, perhaps, because Rhode Island minister Samuel Hopkins had began preaching against slavery as an un-Christian practice in the 1770s. This actually led to the earliest movement opposing slavery in the American colonies. As a result of Hopkins’s and others’ activism, slavery was outlawed in Massachusetts around 1783.

Back in North Yarmouth, 25-year-old Phillis was therefore legally emancipated. But alone and without any means of support she had few options. So she joined the Church in 1784 and continued to live with and work for the Gilmans. She had a room in the ell of the Gilman house, which stands today near the intersection of Route 88 and Gilman Road.

Six years later, in 1790, Elizabeth Gilman died in childbirth at age 43. She left behind seven children, from 18-year-old Joseph to the newborn Samuel. It was therefore Phillis who raised the children for the next 22 years. She “remained a faithful servant and counsellor [sic] of the family until her death” on March 2, 1812 at the age of 54.

Yet at her death Phillis was not buried in the Old Ledge Cemetery in Yarmouth where the Gilman family was buried, close to their home (left).

Yet at her death Phillis was not buried in the Old Ledge Cemetery in Yarmouth where the Gilman family was buried, close to their home (left).

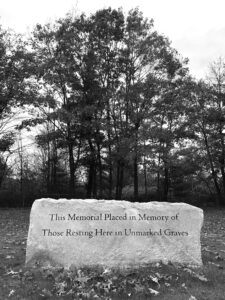

Instead, her body was brought several miles inland to the “pauper” section of Walnut Hill Cemetery in current North Yarmouth. People living in both current Yarmouth and North Yarmouth were buried at Walnut Hill presumably because the more prominent cemeteries in Yarmouth did not allot space for the poor.

Phillis was interred in Walnut Hill in an unmarked grave. After many years, the pauper section, thanks to the efforts of NYHS volunteer Susie Doyle and our Town Clerk Debbie Grover, finally has a marker.

The burial of Phillis with paupers is certainly indicative of attitudes towards “Negroes” at that time. Not only was she Black, she was presumably unmarried, owned no property, and had been a servant all her life. Perhaps in the eyes of the Gilman family, her burial among paupers was proper. There is no mention of Phillis in the Care of the Poor records of coffin-making or grave-digging as there are for other town paupers—that at least would have given us some details of her death. Presumably the Gilmans paid for these services privately. But ironically it means that Phillis is mostly missing from the historical record.

Few Personal Details

There is much work to be done about the very early Black population of the North Yarmouth area. H.H. Price’s massive Maine’s Visible Black History has a few references to Yarmouth but none to our town. Blacks existed in the margins of society; their lives were little recorded.

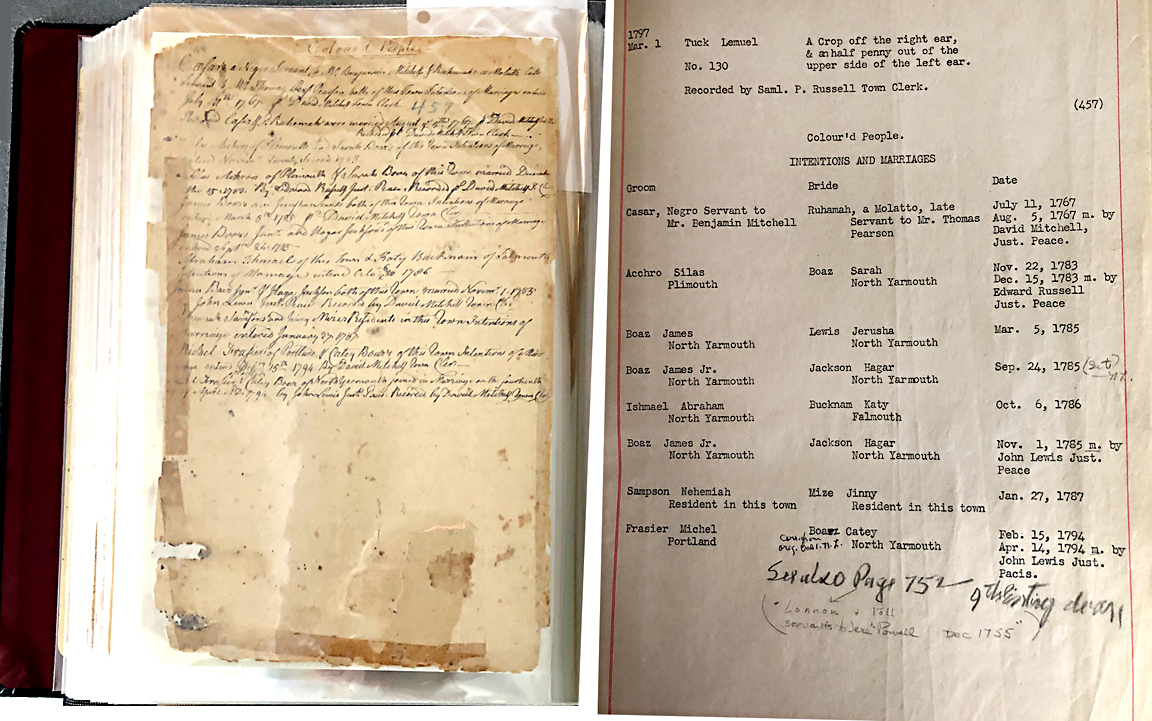

However, our ancient Town Records do give us a few names and details, recorded on one page separate from the rest of the town’s early vital records. About a half dozen names of early Black residents are written into the record, waiting for further research. At NYHS’s Abolition and the Underground Railroad in Maine program this past April 12, we were able to put this page up on our the screen for our Zoom participants to see.

History shows that few places in the United States were exempt from slavery’s reach. North Yarmouth is certainly not one. We have the records to show it.

Thanks to Dr. Mary Freeman, University of Maine; Holly Hurd; Hannah Austin; and Sue Clukey for research that contributed to this post.