A little more than a century ago the world experienced the deadliest flu in modern history. It spread around the planet, and one of every three people was ultimately infected with the virus. An estimated 50 million people died, but since many cases went unreported it is likely that the numbers were even higher. U.S. fatalities topped 675,000, and Maine reported more than 5,000 deaths.

Reading back into time, there are many facts about that virus which resonate today:

• The Spanish Flu did not originate in Spain. It became known as the Spanish Influenza because Spanish news agencies were alone in reporting the outbreak. Other countries stayed mum because they didn’t want to dampen morale during WWl.

• In Maine there was considerable disagreement about the severity of the influenza problem, and many questioned the need to take precautionary steps. Initially, many churches across the state disregarded orders to refrain from meeting.

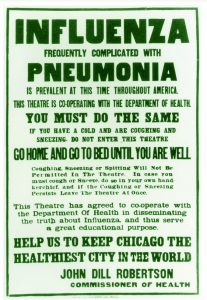

• There were laws enacted to limit the virus’ spread. For example, anti-spitting laws were strictly enforced in cities across the U.S., including in Portland.

• Aroostook County had the highest reported death rate in Maine.

• Many influenza deaths may have been caused or hastened by aspirin poisoning. Trademarked by Bayer in 1899, aspirin was prescribed to alleviate the flu’s symptoms, often at much higher dosages than we now know to be safe.

• The Women’s suffrage movement benefited from the pandemic, as many people thought women had proven their value by providing nursing care during the outbreak and by working in World War I military support positions.

Deaths in North Yarmouth

According to the 1918 and 1919 North Yarmouth Town Reports, only two deaths in town were attributed to the Spanish Influenza. Each of those deaths occurred at the height of the pandemic, in October, 1918. A majority of people killed by the disease were in the prime of life—20-40 year olds, and those who died in North Yarmouth were no exception.

The first in-town death attributed to “the grip” was Bertha Beal Dobson, on October 7, 1918. Bertha’s death records state that she was ill for four days—but less than one month prior she had given birth to her seventh child, Mildred Myrtle Dobson.

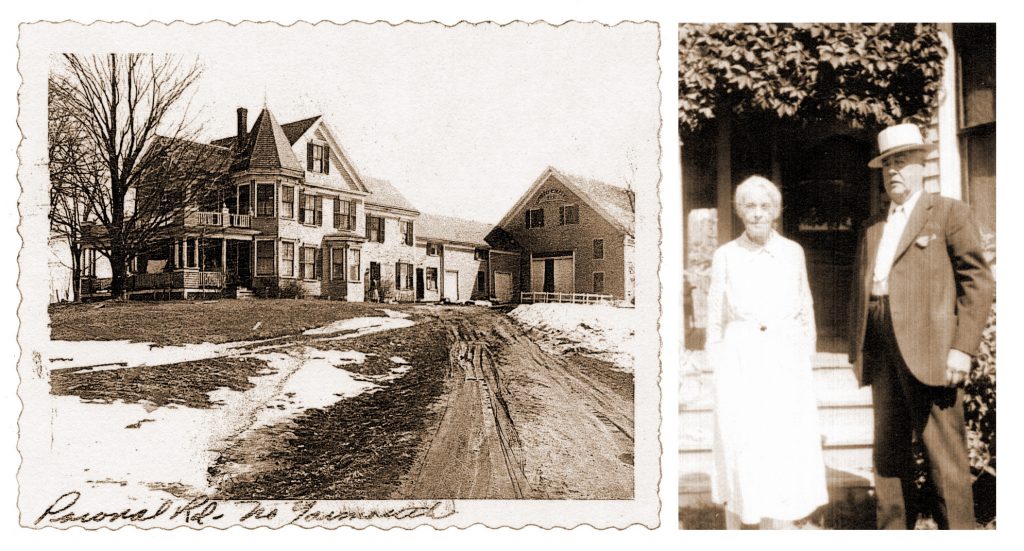

When Bertha died, she and her husband Irvine had been married almost 12 years and had moved to a farm on Royal Road only four years before. Irvine was left with a newborn and six young children ranging in age from 2-11. On October 9, two days after her death, Bertha was buried at Riverside Cemetery in Yarmouth.

. . .

Pneumonia, pregnancy, tuberculosis, and heart disease were the leading associated causes of influenza death, and it is possible that other North Yarmouth deaths attributed to those causes co-occurred with influenza.

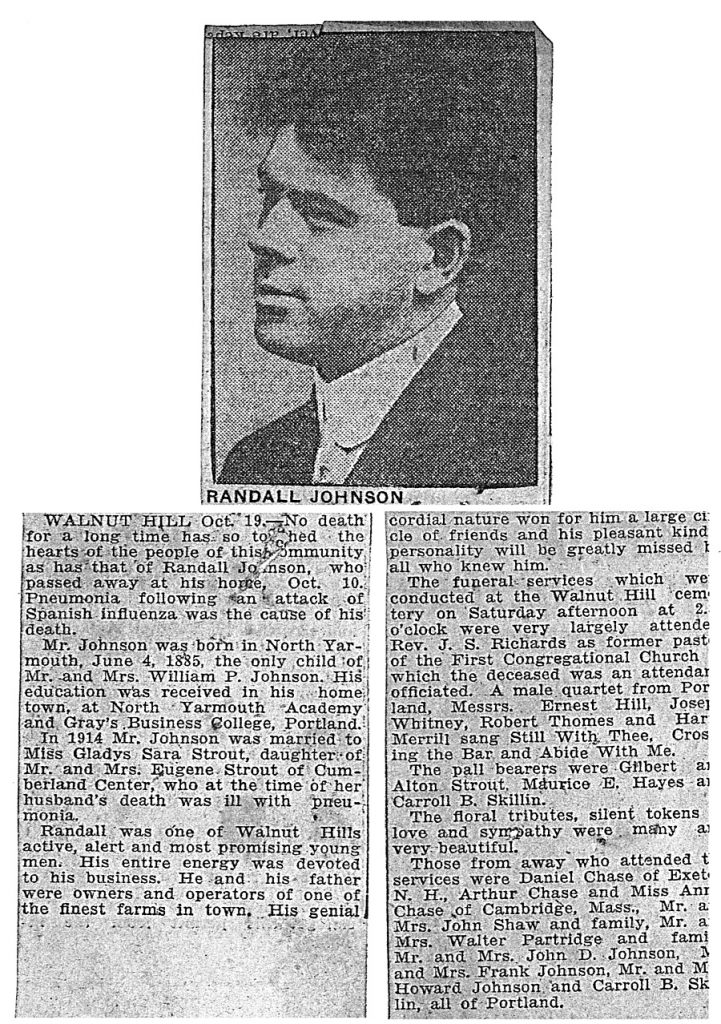

Randall Johnson was 33 when he died on Thursday, October 10, 1918. His death records indicate that the cause of his demise was influenza, followed by pneumonia. From beginning to end, Randall Johnson’s illness lasted 12 days, and his death record specifically states that where the disease was contracted was unknown. Randall was the the only child of Elizabeth and William P. Johnson.

At the time, funerals were being banned in Portland; but in North Yarmouth Johnson’s funeral appears to be a large gathering, with many out-of-town attendees. He was buried at Walnut Hill Cemetery on Saturday, October 12, 1918, two days after his death.

. . .

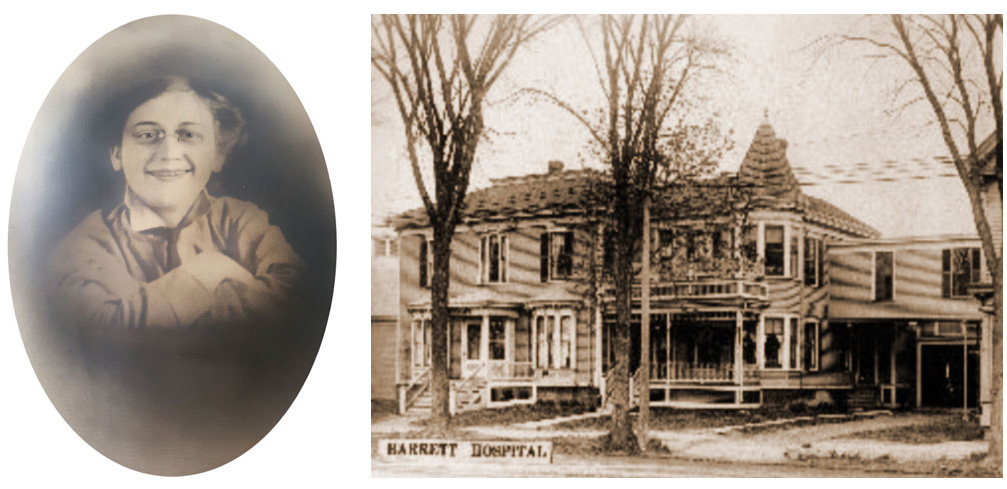

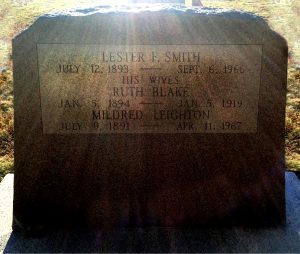

Pregnancy was a contributing cause to the death of another North Yarmouth citizen. Ruth Blake Smith, the first wife of North Yarmouth storeowner Lester Smith, gave birth to Harold, her third child, on June 4, 1918. Harold was delivered by Dr. Felix Barrett at Barrett Hospital in Westbrook.

After Harold’s birth Ruth remained in Westbrook under the care of her sister, Margaret Coffin. Ruth’s granddaughters, Peggy Leighton and longtime MSAD#51 teacher Judy Maddox, recall hearing that their grandmother never regained her strength after the baby’s birth. She caught a cold, followed by pneumonia, and ultimately influenza, and it isn’t clear whether she ever returned to her home and family in North Yarmouth. Her death records state that she was in Westbrook seven weeks prior to her death. Dr. Barrett was the physician who reported her demise on January 5, 1919—also the date of her twenty-fifth birthday. She is buried in Walnut Hill Cemetery.

. . .

Aside from the above information, NYHS knows little about how the Spanish Influenza affected the lives of townspeople. The School Superintendent’s comments in the 1919 town report allude to many interruptions in the school year due to “illness of students and teachers,” but a similar comment was made the year before the pandemic’s start, so we can’t assume with certainty that his 1919 comment is related to the flu rather than typical winter ailments. Since Covid-19 is preventing us from accessing diaries, newspaper clippings, and other records in the society’s archives, learning more will have to wait until the 2020 pandemic is over. We can, however, collect stories from you. If you are related to Bertha, Randall, or Ruth, or if you know other influenza stories, we’d love to hear from you.

—Dixie Hayes